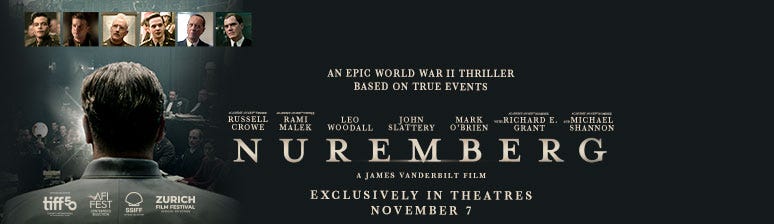

how Nuremberg (2025) is symptomatic of how we discuss history

what this film gets wrong about exactly what it says it represents

If there’s one thing about me, it’s that I grew up a huge nerd about Weimar Germany, Nazi Germany, World War II, etc. I could be found reading books about it on holiday, went to all the exhibits I could find, and then ended up studying it at both GCSE and A Level. So, Nuremberg (2025) was an obvious watch for me.

Nuremberg is based around the Nuremberg trials, which famously put some of the most involved Nazis on the stand (excluding Hitler, Goebbels, and Himmler, all of whom had died by suicide before the trials) through international criminal trials, by the UK, USA, France and the Soviet Union. They tried 22 different individuals, largely for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

In the film, we follow a psychiatrist (Douglas Kelley, portrayed by Rami Malek) who is to evaluate and monitor the Nazis being held in prison before their trials. His goal is, essentially, to keep them alive. He talks to them often, particular Hermann Goring, and he even interacts with Goring’s family and passes letters back and forth.

Ultimately, Goring is sentenced to hanging but dies by suicide moments before. Kelley then uses his experiences to write a book, which he struggles to promote due to the trauma inflicted. The film closes with him being kicked out a radio station, and the intertitles tell us that the real Kelley struggled with alcoholism before dying the exact same way as Goring.

This is not a bad film - some elements are incredibly emotional and genuine. The trials themselves are done rather well; the footage of the Holocaust combined with the reactions of the cast is compelling and gives you a moment to be reminded of the absolute reality this film is based in. Overall, although the run time is arguably too long, the film certainly has merits.

For me, though, there are glaring issues with this film in how we continue to portray history.

The Bechdel Test and women in Nuremberg

If you have never heard of the Bechdel test, this is a benchmark put forward for how films portray women: two women must have a conversation with each other about something other than a man.

Nuremberg glaringly fails the Bechdel test. There are three notable women in this cast, and they are consistently only used to further the plot of the men: one, the wife of Goring, one, a journalist, and one, a secretary. If I remember rightly, the only moment when two non-males talk to each other is the wife and daughter of Goring - never two adults.

This is horrifically symptomatic of how we talk about history. Although, of course, men did overshadow women largely, and there were still roles or jobs they did not tend to take up, women were heavily involved in the war and its aftermath. This includes at Nuremberg itself: women played many roles in the trials, including as lawyers, such as Katherine Fite who wrote detailed letters about her time there. Her letters say that she engineered an interrogation from Wilhelm Frick, giving questions to the interrogator1.

Elsewhere, Cecelia Goetz was a female prosecutor who was the only woman to read an opening statement at Nuremberg for the trial of the Krupp Group’s armament of the German military2, and Irma Von Nunes has been reported as the first woman involved in the war crimes trials3. Many other women served as interpreters or translators. Almost the only role they did not serve in was as judges.

Nuremberg follows the pattern that so much of history, and media describing it, does. It completely leaves behind the role of women, and there is no effort to fix that. It does not take more than a quick Google to see that there were many women involved specifically in the trials, let alone the war effort overall. As a brand new film, and one focusing in so closely on a specific part of the post-war impact, this was an excellent opportunity to highlight, not erase, the importance of women.

The women who do feature are largely meek and timid - Elsie Douglas, portrayed by Wrenn Schmidt, has a key role in supporting Robert Jackson, the main prosecutor. She is rarely shown as an equal in the process, both in the script and in the cinematography: always off to the side, slightly behind the men.

I’m sure many would argue this does not matter, or that they are cramming a lot of history into a short film. But this erasure is symptomatic of how the rest of the society views women in history: as non-existent, as not playing a role. It matters that we do not further these myths as we create more media based on incidents like Nuremberg.

Marginalising the marginalised

Away from portrayal of women in the film through the characters, many marginalised groups are left behind in the discussion of the Holocaust. It is, of course, most critical that Jewish people are discussed in this context, and this seemed to be done well (but I am not Jewish, so I would be interested to know if this is seen as actually the case). As previously mentioned, the footage shown is harrowing and given extensive time for the audience to genuinely process and reflect on.

What was particularly jarring though, to me, was the speech by the prosecutor that listed groups impacted by the Holocaust when talking to Goring on the stand. He listed Jewish people first, crucially, but goes on to list “artists, writers and scientists”, with no mention of groups such as disabled people or gay people.

This is another example of where the film misses the mark in how we discuss and remember history. Naming enough impacted groups to be able to name writers and scientists, but not having the room to mention key minority groups who were persecuted and killed, is the sort of erasure that these groups still experience today - and is history that deserves to be taught.

Is there a risk of over-humanising?

Nuremberg seems to set out to show the parallels between Kelley and the Nazis, particularly Goring - we spend huge amounts of the film with the two of them chatting, sharing memories, and such. For Kelley, it’s apparently just a thought exercise and a fascination, but as the film slips by, their relationship deepens and he spends several scenes with the wife and daughter.

The issue we come to, ultimately, is that when Kelley watches the footage of the Holocaust during the trials, he is shocked. He accuses Goring during his final visit to him and seems to have to come to terms with this reality. To me, this is fascinating - after watching, I could not tell if the intention here was to show the genuine shock of many at the trials, or to show how easy it is to be disarmed when we get to know someone.

Intention aside, it came across rather badly - perhaps like Kelley had believed Goring was a better man than he was, or that he had lost focus. The intertitles at the end and the scene of Kelley at the radio station show that the real Kelley spent the rest of his life warning about future regimes and how easy it is for them to occur - but this is not how that last visit scene really came across.

It’s an interesting question, to me, of: do we humanise these individuals in order to show how easy it is for these things to happen (and that the Nazis were, in fact, still human) or is this a risky portrayal that leaves viewers feel empathy they ought not to? I don’t think Nuremberg managed to straddle that line in a way that worked.

A film that wants to believe it hasn’t fallen into its own traps

Nuremberg is a film that aims to lift the lid on a part of World War II and its aftermath that is often not given much airtime; though critical to how the world responded and how wars are looked at and dealt with now, it is still underdiscussed and often untaught. But throughout, there are themes all around being exposing the truth and realities of the time - all the while, there are ways the film is doing that itself.

Erasing marginalised people and particularly the lack of any care for the stories of women is symptomatic of exactly how we treat history: completely lacking and perpetuating of misconceptions.

If you made it this far, thank you so much for reading! If you’d like to support me, you can become a free or paid subscriber, or buy me a coffee (a pink lemonade, actually)💫

Things I wrote lately ✍🏻

The arts scene is harming marginalised communities – where do we go from here?

On how the arts scenes is continuing to marginalise so many people, including through funding, representation, and inaccessibility.

What’s been all consuming lately?📖

I went to see Lorde a few weeks ago and it’s genuinely all I’ve been able to think about. No one puts on a show quite like it. Probably the most engaged crowd I’ve been in in a long time.

Now You See Me, Now You Don’t - I’m a hugeee fan of these silly woke magic movies and the new one is no exception. Lots of the reviews are bad, but I think we should let films be fun again!

Hadestown on the West End - such a mesmerising show. I got to see the icon that is Allie Daniel as Hermes, and it hooked me in completely.

We saw The Hunger Games on Stage the same day. I would honestly say don’t bother. I’m still thinking about it now, but not for good reasons. Full review on my Instagram.

Guepet, H. (2025) The women prosecutors at the Nuremberg Trials, The National WWII Museum | New Orleans.

Public lecture by Diane Maria Amann (2018) shared in Women at Nuremberg: Cecelia Goetz, USC Shoah Foundation.

Diane Marie Amann, Portraits of Women at Nuremberg (2010)